The Journal of Midshipman C.W. Poynter

(The Hakluyt Society 2000)

C. W. Poynter’s journal is the only surviving first-hand account of Bransfield’s historic voyage of discovery. It only came to light in the 1990s when it was discovered amongst the effects of an estate in Blenheim, New Zealand, originally belonging to the Clouston family and was bought by the Turnbull Library in New Zealand. It was subsequently reproduced by The Hakluyt Society 2000 (ISBN 0 904180 62 X)

For a detailed description of the journal, it’s history and Charles Poynter check out A.E.G. Jones’ 1997 paper.

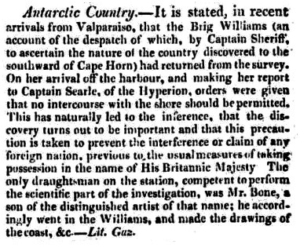

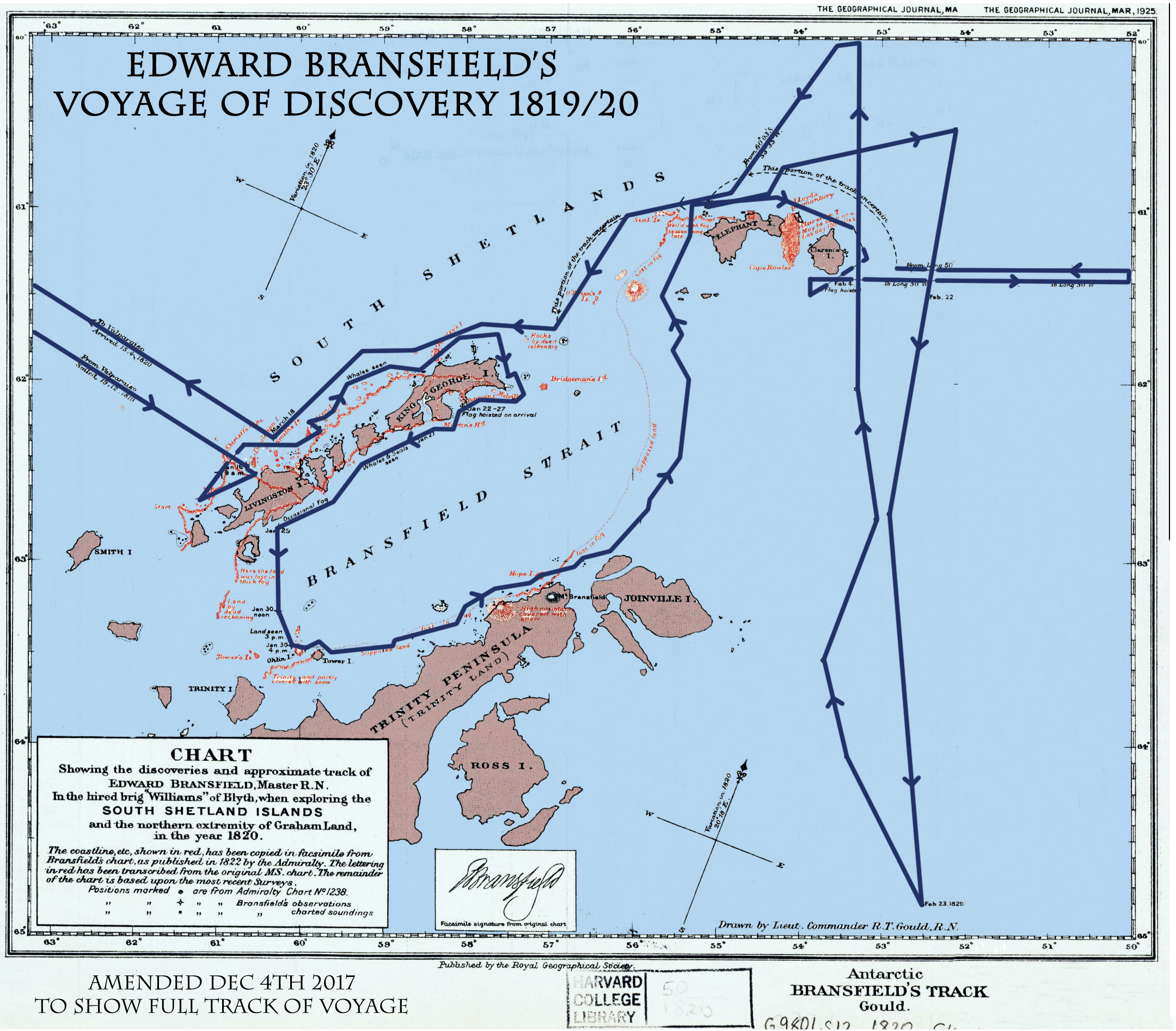

Bransfield’s expedition had discovered a rocky chunk of the north-western shore of the Antarctic Peninsula which was named Trinity Land. A small nearby island was called Tower Island and in the distance the party could clearly make out an imposing snow-capped mountain. The 760m/2,500 ft peak is today named Mount Bransfield.

The Williams was rocked by gales and very rough seas over the following weeks as Bransfield and his crew endeavoured to extend their new discoveries. Occasionally, the ship broke into the Weddell Sea or ran along the eastern coast of the Peninsula and on 23th February 1820 the Williams reached 64° 56’ S. At one point, Williams steered close to charted some of the coastline of Elephant Island where, a century later, Shackleton’s men would be marooned after the sinking his ship, Endurance.

Bransfield turned north, (his decision partly made because some of his crew were dressed for Valparaiso weather and not the Antarctic weather for the whole trip!), and finished in Valparaiso on 16th April 1820 at the end of an epic and hugely challenging voyage. Not a single man was lost.