However, the long debate over who made the first discovery was severely hampered by the loss of crucial documents. The log book of Williams disappeared and has never been found, which left Bransfield’s claim reliant on the surviving charts and some magazine articles about the expedition from the 1820s. But the most significant development was the discovery in the 1990s of the journal kept by Midshipman Poynter, which contains the most valuable first-hand account of the expedition.

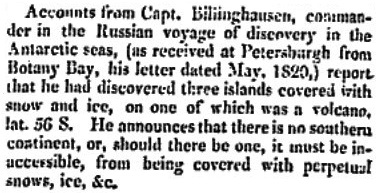

Bellingshausen’s account of his 1819-21 expedition did not appear until a decade later in 1831 and a detailed English language version did not appear for well over 100 years in 1945.

Rip Bulkeley’s Research

More recently, the author Rip Bulkeley has conducted the most thorough investigation ever made in English. Bulkeley received the Anderson Medal from the Society of Nautical Research for his book ‘Bellingshausen & the Russian Antarctic Expedition 1819-20’ (Palgrave Macmillan 2014) ISBN 978-1-137-40217-2. In striking similarity to the fate of Bransfield’s papers, Bulkeley reported that the original manuscript of Bellingshausen’s book about the expedition, his journals and the naval records have all disappeared.

From his research, Bulkeley said there were “reasonable doubts” about the Russian claim and that “…Bellingshausen was not the first commander to see the Antarctic mainland…” He concludes: “…the Russians did not see main ice until mid-February 1820, when they became the second expedition after Bransfield, now known to have seen the mainland.”

The following is the relevant section summarising the case for Bransfield from his book:

“To end this section, so many people have been exercised about a single aspect of the Bellingshausen expedition that the author feels obliged to summarize his reasons for concluding that Bellingshausen was not the first commander to see the Antarctic mainland, even if we accept that he could have done so by seeing one of its major peripheral ice features. First, it was argued in Chapter 4 that Bellingshausen and his comrades had a clear enough ice vocabulary to tell and state the difference between a continuous ice field containing icebergs, and the massive cliffs of ‘main ice’, which was expected to resemble an ordinary mainland apart from its material. For continuous ice, which could be penetrated by icebergs but only to a limited extent by small wooden ships, there were books available, some of them in Russian(Lomonosov,1952;Phipps,1774;Scoresby,1818); next, the vocabulary was small and easy to master; and third, Bellingshausen shows every sign of using it consistently. For main ice, a theory of polar ice caps had been developing for 150 years and was represented in one of the latest maps of the southern hemisphere. Meanwhile a parallel, vaguer theory about land-like ice masses, also known as ‘main ice’, had evolved in the whale fishery and had recently been made available to scientists and explorers(Phipps,1774;Scoresby,1818;J.Ross,1819).

‘Next, the extensive and fluctuating ice fields around Antarctica are not so obviously part of the continent as its (hitherto) more solid and permanent ice barriers, sheets and tongues, which have been named as geographical features. Cook saw the ice fields, but historians do not believe he got close enough to see one of the major ice features. For that reason he is not thought to have discovered Antarctica. Those who, unlike the author, discount the tradition of early discovery (above), have therefore been anxious to determine whether or not the Russian expedition sighted a major ice feature on 16(28) January 1820,twodays before Bransfield and Smith sighted what is now called Mount Bransfield on the Antarctic Peninsula.’

‘That question comes down to a choice between Bellingshausen’s statements, supported by others, that as in early January so too on 16(28)January 1820 what they saw were ‘ice hills in an ice field’, or alternatively, Lazarev’s reference to ‘main ice of extraordinary height’ in a private letter written 20 months after the event, one in which Lazarev misstated several other, less important matters. Because it was retrospective, unsupported by other witnesses, and associated with demonstrable errors, Lazarev’s description of 16(28) January 1820 stands open to reasonable doubt. The author has therefore accepted that the account left by Bellingshausen, with corroboration from Simonov and Novosil’skii, is the more convincing alternative, and has concluded that the Russians did not see main ice until mid-February 1820, when they became the second expedition, after Bransfield, now known to have seen the mainland.”

Bransfield left the navy in the 1820s and returned to the sea as a merchant mariner, while Bellingshausen resumed in career in the Russian navy. Edward Bransfield died a forgotten man in Brighton on October 31, 1852 at the age of 67. He outlived Bellingshausen, who died on January 25, 1852, by nine months.

See: Bellingshausen and the Russian Antarctic Expedition, 1819–21 by R. Bulkeley, published by Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. (ISBN 978-1-137-40217-2)